Category: pondering

-

Link: AI is Destroying the University and Learning Itself

https://www.currentaffairs.org/news/ai-is-destroying-the-university-and-learning-itself

-

Link: Do Not Worry That Generative AI May Compromise Human Creativity or Intelligence in the Future: It Already Has

Sternberg RJ. Do Not Worry That Generative AI May Compromise Human Creativity or Intelligence in the Future: It Already Has. J Intell. 2024 Jul 19;12(7):69. doi: 10.3390/jintelligence12070069. PMID: 39057189; PMCID: PMC11278271.

-

The Silicon Sovereign: The Origins, Rise, and Evolution of the Google Tensor Processing Unit (written by Gemini 3.0)

Executive Summary The history of digital computation has been dominated by the paradigm of general-purpose processing. For nearly half a century, the Central Processing Unit (CPU) served as the universal engine of the information age. This universality was its greatest strength and, eventually, its critical weakness. As the mid-2010s approached, the tech industry faced a…

-

Building products with Claude Code, even for non engineers

I have worked in high tech for 30 years, building products for public companies and training thousands of software engineers to be productive. In 202, I have tutored 331 hours with tutor middle school, highschool, college students in computer science. My most recent students are adults who are not computer engineers but they want to…

-

What could be a possible positive outcome of the AI Bubble

I have been using AI Coding tools daily to prototype and launch productive level apps and websites. I have also been tutoring non-computer science folks through my Wyzant tutoring business how how to use AI to product the app that they have always wish would exist in the world. One high school student is building…

-

Tutoring student in C and solving project problems

Today I was working on the students who in college was struggling with being able to read a project spec or a project problem set and knowing where to go and tackle the problem. So what I coach them on doing is rather than focusing on the larger problem sets, try to break down the…

-

Tennis being my new racket sports of choice

I’ve spent a significant portion of my life dedicated to the sport of badminton. The fast-paced, precision-driven nature of the game has always appealed to the software engineer in me. The thrill of a perfectly executed drop shot, the satisfaction of a powerful smash, and the camaraderie of the badminton community have been a constant…

-

From Perl Scripts at Yahoo! to AI-Powered Flutter Apps

I was thinking the other day about how much has changed since I started at Yahoo! back in ’99. Back then, we were building the internet’s infrastructure with Perl scripts, find and grep commands, and a whole lot of grit. We were the ones in the machine, making it work, scaling it to millions of…

-

Maybe goodbye to full time work

What started out as a six month sabbatical ended up as a two year break from full-time work. My last day at Splunk was August 3rd, 2023. What has Tony been doing with all this free time? My update 15 months in here on LinkedIn My update 1 year in here on LinkedIn Here at…

-

Love of tennis

-

Rolling up my sleeves and taking care of business

This morning, it was time to take care of the staircase that looks worn down and on the verge of breaking down.

-

Best Alternative To Google Podcast

AntennaPod!

-

U.S vs Apple 2024

The price of iPhones over time

-

link: NYT: I Live in My Car

-

Los Angeles food: Boba Bunny

-

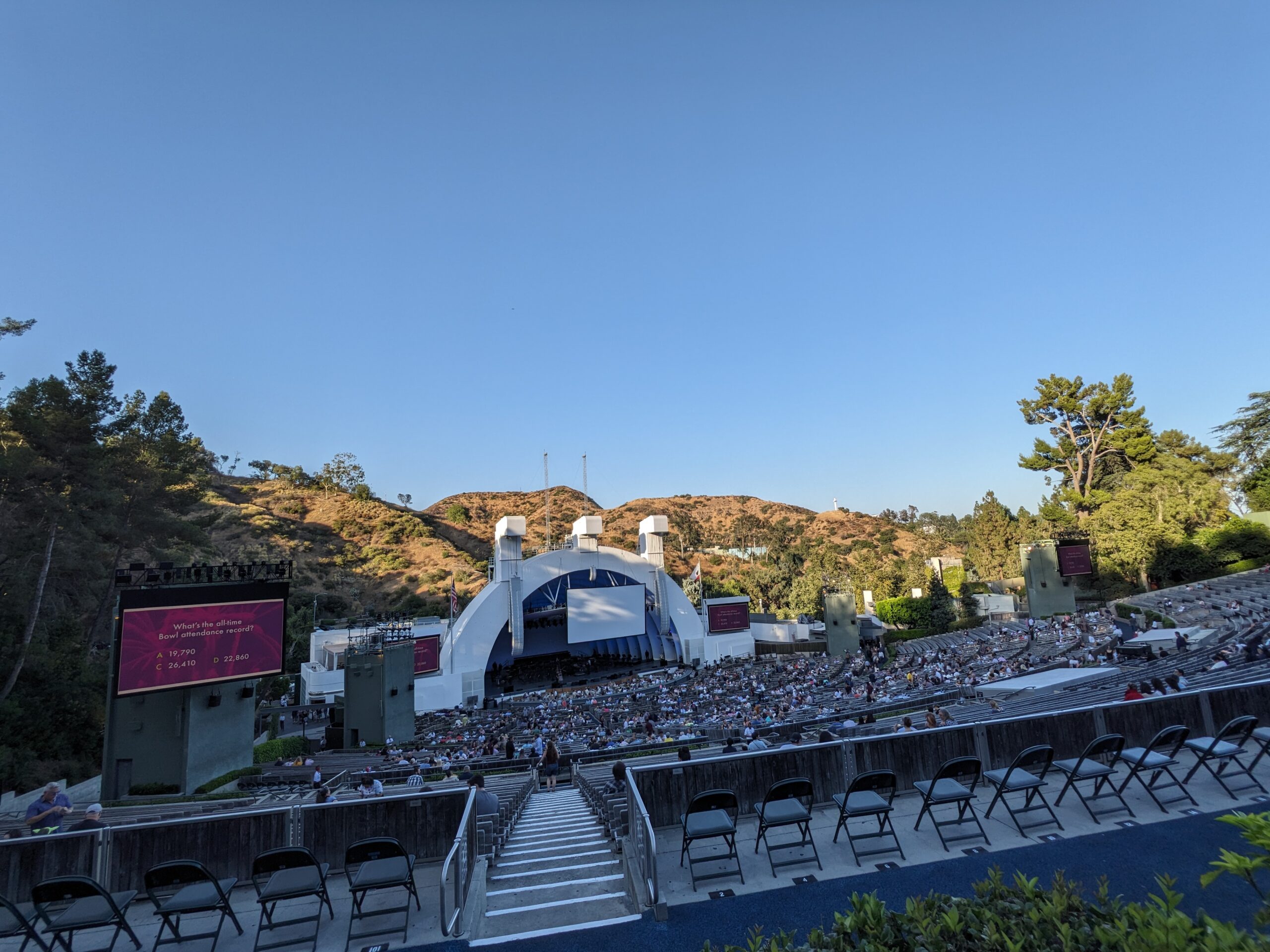

Hollywood Bowl

-

link: Transformers: the Google scientists who pioneered an AI revolution

Transformers: the Google scientists who pioneered an AI revolution

-

link: Why would anyone make a website in 2023? Squarespace CEO Anthony Casalena has some ideas

https://www.theverge.com/23795154/squarespace-ai-seo-web-social-algorithms-anthony-casalena

-

Photos: hiking in Cool, California

-

link: 5 reasons audio is better than video

https://writtenandrecorded.com/podcasting/5-reasons-audio-better-than-video/

-

ChatGPT coding challenge 2022.12.11.1 – cypress.io

Write a cypress.io test open the browser to Google, search for 100″ TV and click on the first advertisement shown chatGPT is great at scaffolding up some code, then the engineers comes in and does cleaning up. thank you robot See this little screen recording of me running the cypress.io script https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Cq-k77AsiIGhFD0cscWSZX9Ed02sp6bm/view?usp=share_link

-

ChatGPT coding challenge 2022.12.11 – complete game of Math24

“Write a GoLang program that can play the game of Math 24 and if the players gets the wrong answer, provide the answer.” ChatGPT Answer (limitation, not able to validate anything more than simple addition)

-

My Next Role 2022

It’s that time, the 7-year job itch. As a rule of thumb, I tell myself to be open to exploring opportunities and not stay in one company for too long. I was at Yahoo for way too long (16 years) and now with Splunk for 7 years. It’s healthy to be open to different roles…

-

15 years badminton -> 3 years tennis

After playing badminton for over 15 years, for the last 2 years, I have become a daily tennis player. Join me at https://sf-tennis.org!

-

San Francisco: inner Sunset 9th Avenue

Start your morning around 8:30am 1. Sunset Farmer’s market 2. Pastries and coffee at Arizmenti Bakery – cherry cornmeal scones, berry muffins

-

Movie: Find me

Emotional indie movie that captures you with beautiful national park and a touching story https://www.imdb.com/title/tt6740154/

-

“Whether you believe you can do a thing or not, you are right” – Henry Ford

-

link: CodeKraft – 9 multipliers for boosting your team’s productivity

-

link: The Heilmeier Catechism (DARPA)

Sharing a link https://www.darpa.mil/work-with-us/heilmeier-catechism DARPA operates on the principle that generating big rewards requires taking big risks. But how does the Agency determine what risks are worth taking? George H. Heilmeier, a former DARPA director (1975-1977), crafted a set of questions known as the “Heilmeier Catechism” to help Agency officials think through and evaluate proposed…

-

Chances of landing a position in big tech

In a response to this LinkedIn post. Sometimes I think people in tech companies treat interviewing like a hazing ritual because they went through the same process, they think the next set of new hires also needs to jump through the same hoops. For junior engineering positions, each open position gets 200+ resumes, and they…

-

Book: The Witch’s Heart

First book I have read about the Nordic mythology and I love the normalcy of the unusual babies.